Religion and science are often seen as incompatible, but thatŌĆÖs never been how Detroit native Guy Consolmagno felt. The 68-year-old, born in Harper Woods and raised in Birmingham, always thought his pursuit of understanding how the universe functions was, in fact, also about becoming closer to God.

Both passions were born in Michigan where, by day, he attended the University of Detroit Jesuit High School and by night he gazed at the heavens through a portable telescope he bought with trading stamps.

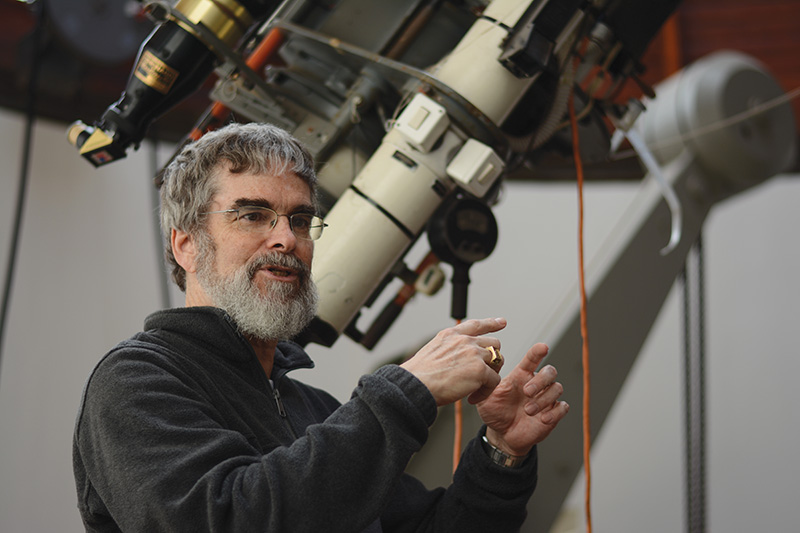

After decades as a research astronomer for the Vatican, where he has long been curator of the ChurchŌĆÖs vast meteorite collection, the Jesuit brother was tapped by Pope Francis in 2015 to be the director of the Vatican Observatory. By then, heŌĆÖd become a much-loved public speaker on how he reconciles faith and fact, earning the Carl Sagan Medal for his scientific evangelism from the American Astronomical Society.

Consolmagno, a layperson who joined the Jesuit order in 1989 and committed to the same vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience as ordained members, spoke to us about his Detroit upbringing, his ties to three popes, and what heŌĆÖd love to do on the moon. Usually, he lives in Rome, but he has been living at a church facility in Arizona, where he was visiting when COVID-19 hit.

║┌┴Ž═° Detroit: How did you end up in astronomy?

Brother Guy Consolmagno: I went to Boston College with an idea of going into journalism but had a terrible time because everybody else was busy drinking and having a good time, and I found that boring. To get away, I figured I would join the Jesuits, but the Jesuits said I had to pray until I felt called by God. I went to my room and sat on the floor waiting. Of course, nothing happened. Then this thought popped into my head that a priest takes care of people with problems, and I realized IŌĆÖd be terrible as a priest. I had no patience with that sort of nonsense. So where was I happy? What did I enjoy? I was happy visiting my best friend from high school at MIT. So, I transferred to MIT and I picked earth and planetary science because I saw the word ŌĆ£planetŌĆØ and thought that was astronomy. I had no idea it was geology and that I would become a planetary geologist. ItŌĆÖs funny how you make crazy decisions for all the wrong reasons and they turn out right.

Does it bother you that humans spend so much money sending things into space when we have so many needs on Earth?

It was why I briefly left science. I was 30, a postdoctoral fellow at MIT, and I could not justify wasting my life worrying about the moons of Jupiter. I joined the Peace Corps, and they sent me to Kenya. I discovered that the people in Kenya also wanted me to tell them about the planets, to look through my telescope and be amazed by the rings of Saturn. It dawned on me that asking the bigger questions ŌĆö what is in the universe? how do I fit in? ŌĆö is essential to being human. And we are rich enough that we can do both. NASAŌĆÖs budget is 0.5 percent of the U.S. governmentŌĆÖs budget. The Vatican ObservatoryŌĆÖs budget is 0.5 percent of the Vatican city-stateŌĆÖs budget. So, really, weŌĆÖre not spending much money.

What do you remember about the moon landing?

I was in high school in Detroit. I grew up watching every space launch on TV, or theyŌĆÖd bring a TV into our classrooms. I used a cassette tape to record the landing of Apollo 11 off our television set. It was something very real to me and real to everybody. My dad worked in communications at Chrysler, and Chrysler built a number of rockets ŌĆö the Redstone rockets and the Saturn One rockets. Right now, IŌĆÖm holding in my hand a little piece of Lucite with a first day-of-issue stamp dated Cape Canaveral, Feb. 20, 1962, Project Mercury. The first couple of Mercury rockets that launched people into suborbital orbits were Redstone rockets made by Chrysler. We knew the people who were doing that.

Is it practical to colonize the moon or Mars?

I do not want to see humans on Mars anytime soon because humans leak E. coli and all sorts of other bugs. I want to find out if Mars has its own bugs before we introduce ours. But IŌĆÖd love to visit and maybe live in a small community on the surface of the Moon or under the surface of the moon in one of the lava tubes. IŌĆÖd love to live in a place where the gravity is low enough that you could strap on wings and fly.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs funny how you make crazy decisions for all the wrong reasons and they turn out right.ŌĆØ

ŌĆöBrother Guy Consolmagno

How well do you know the pope?

I wouldnŌĆÖt say weŌĆÖre buddies. The current pope knows my name. I show up and he recognizes me. ItŌĆÖs helpful to have a beard, because it makes you stand out. But, also, weŌĆÖre fellow Jesuits and weŌĆÖve got Jesuit friends in common. IŌĆÖve worked with three popes, and though I was a much more junior scientist when I arrived, they would recognize me. ItŌĆÖs not like I have lunch with them, though.

ThereŌĆÖs talk of putting space facilities around Michigan. Why here?

If youŌĆÖre going to launch a rocket, you want to launch it somewhere where if the rocket fails and it falls down, it doesnŌĆÖt hit anybody or destroy property of people who will sue you. That means being near a body of water. They also tend to launch to the east because you get a little extra oomph from the spin of the earth. The places where theyŌĆÖve launched from in the U.P. in the 1970s were over Lake Superior. The other port theyŌĆÖre talking about near Alpena would launch eastward over Lake Huron.

What did Michigan give you?

The great thing that I got out of being a Detroiter was a sense of a confidence that I could do anything, without the arrogance of thinking that I could do it just because I was born in the right place at the right time. It has kept me from the extremes of being an extreme snob who thinks science has all the answers or an extreme religious fanatic who thinks that my understanding of God must be right. It was a very practical, down-to-earth kind of upbringing. The kids I played with worked at Chrysler; their dads were blue-collar workers. And we had a sense of being close to nature that you get having summer cottages and having lakes nearby as well as a respect for the technology that goes into automobiles and spacecraft.

Do you miss our part of the world?

Oh, yes. My dream when I retire would be to come back to Detroit. I would love to teach at the University of Detroit or some other Jesuit institution. Though itŌĆÖs been 50 years since IŌĆÖve lived there, I still love it. I miss the apple-picking and cider and donuts. I miss rooting for the Tigers.

|

| ╠² |

|